The Lattices at Yin Yu Tang - and Possible Parallels in Mainland Chinese Beadwork

On a working trip to Boston a few months ago, I spent a day in Salem, MA visiting the Peabody Essex Museum.

The Peabody is celebrated for its extensive collection of artifacts from China – a byproduuct of Salem’s former position as a major port for American ships sailing to the Orient and back, laden with foreign goods.

The largest of those artifacts is Yin Yu Tang, a two-story, 16-bedroom house that originally stood in Huang Cun, a village in Xiuning County of China’s mountainous Anhui Province.

Yin Yu Tang or “Hall of Plentiful Shelter” was built in the late 18th century by a wealthy merchant named Huang who hoped his family would live there for many generations after he died – and they did.

Until the mid-1980, when, lacking amenities such as running water, Yin Yu Tang became vacant. It seemed only a matter of time before the house would be torn down to make way for a more modern structure.

In the mid-1990s, with the help of then-curator Nancy Berliner, the Huang family sold Yin Yu Tang to the Peabody with the wish that the house be preserved long-term.

Yin Yu Tang was carefully deconstructed into manageable pieces and shipped in crates to a Boston-area warehouse. After native Chinese woodworkers renovated rotten beams, the house was reconstructed on the grounds of the Peabody Essex Museum.

Yin Yu Tang opened to the public in 2003. As the only intact example of Chinese vernacular architecture in North America, it has attracted thousands of visitors per year ever since.

Along with the house itself, the Peabody also acquired the genealogical records of the Huang family and the house’s furnishings as they existed in the 1980s.

Acquisitions of this nature helped preserve not just the physical structure of the house, but aspects of its role in staging human lives.

The full story of the house and its relocation to Salem is told in Nancy Berliner’s illustrated book.

Small homey touches abound inside Yin Yu Tang, creating a feeling that the inhabitants will soon return.

Red peppers are set out to dry on a tray; a small shrine stands in one corner of a room; bamboo baskets and auspicious charms hang on walls.

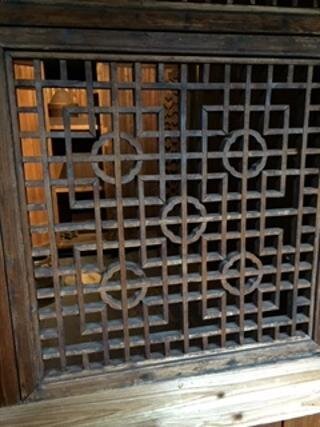

One trip through Yin Yu Tang was not enough for me. I went back the same day for a second, this time to photograph the window and door lattices.

Wooden lattices have been made in China for centuries in a wide variety of designs. Some of them are documented in the publications of American educator Daniel Sheets Dye (1888-1977), among them, Chinese Lattice Designs.

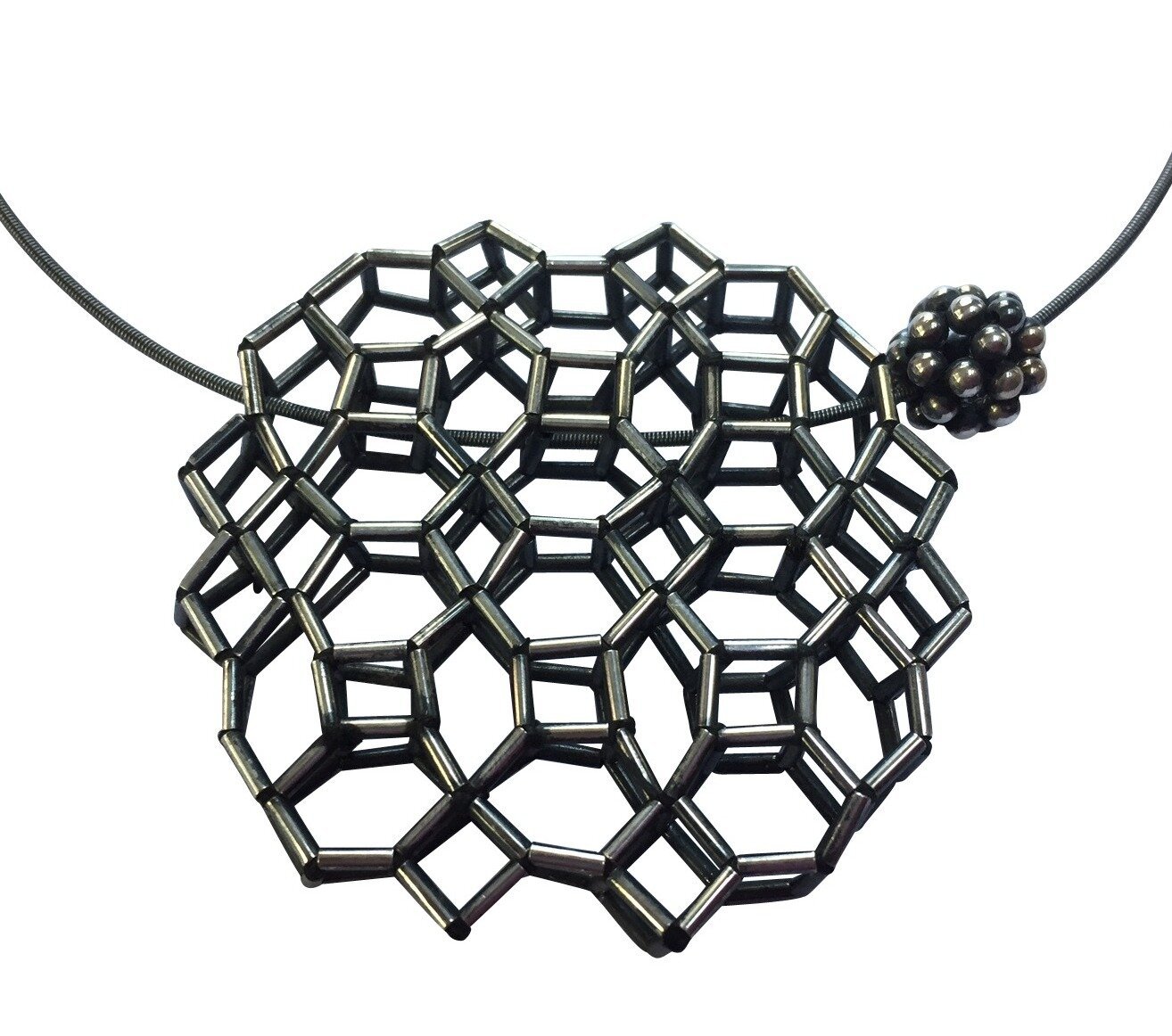

Partly thanks to Dye’s books, I’ve been incorporating lattices into my own work in the last few years, making them from small sterling silver or Czech glass beads. I had wanted to make lattices for years - but in single layers, they were too flimsy. One day it occurred to me to make them double-layered, even though that takes a great deal more time, and the use of a chain-nosed pliers to make the needle go through holes in beads.

I found more inspiration at Yin Yu Tang. Its lattices are diverse and mostly intact. But I don’t mind broken lattices.

Areas of breakage let us see the layers of a piece, where traces of the maker’s hands may remain.

Standing in the courtyard, photographing the lattices, I experienced a minor revelation. A long horizontal lattice high above a wide doorway contained three Chinese characters set against a diagonal grid. This lattice was very hard to photograph. Lights just above it brought unwelcome glare. I couldn’t tell if some of the characters had been damaged. But the middle character seemed to a decorative form of shou or longevity, a very common motif in Chinese decorative art.

Photo of a horizontal wood lattice high above a doorway in the courtyard. On the lattice, three Chinese characters are shown on a diagonal grid. The central character represents shou or longevity, a very common motif in Chinese decorative art. The other characters are harder to decipher. Bright lights a few inches above the characters introduce unwelcome glare. Photo: Valerie Hector.

Two features seemed significant: first, the rectilinear script style in which the characters were rendered and second, their appearance on a diagonal grid.

These features brought to mind a Chinese beaded valance I’d come across some time ago, which probably hung in a doorway. A rather wide doorway, the kind present in a spacious home or ancestral hall.

Valance made of Chinese glass beads plaited with a knotted natural fiber thread (ramie?), featuring auspicious flowering vase motifs flanked by paired Chinese characters. China, ca. 1900-1940. Private collection. Photo: Sanders Visual Images.

The beaded door valance features eight characters also rendered in a rectilinear script style on a diagonal grid formed by a knotted plaiting technique we might think of as macrame. One of the characters represents shou.

I wouldn’t think much of the two parallels — except for the fact that the beaded valance was anecdotally attributed to Anhui province, an attribution I doubted at the time.

Beadwork in Anhui? Who’d heard of that? I hadn’t. Knowing little about Anhui or the many successful merchants who lived there, I assumed there wasn’t beadwork.

Visiting Yin Yu Tang caused me to re-examine my assumptions. It opened my mind to new possibilities.

Clearly, if houses like Yin Yu Tang existed in Anhui, then some of its citizens could have afforded luxury goods such as beadwork.

In fact, it’s tempting to speculate that the beaded valance could have come from a county such as Xiuning, a village such as Huang Cun – or a house such as Yin Yu Tang.

The presence of vase motifs on some of Yin Yu Tang’s lattices and on the beaded valance also gave me pause - though the vases depicted in the Yin Yu Tang lattices are empty, and the vases depicted in the valance are full of flowering plants.

Like the shou motifs, vase motifs are also quite common in Chinese decorative art, where they typically symbolize peace. This might seem a curious connection. But in Chinese, “ping” means “vase” and also “peace.” The two words are homophones.

If forced to decide, I would conclude that the parallels between lattice and valance are mere coincidences borne of my wish to establish a definitive geographical origin for the beaded valance.

Too often, pieces of mainland Chinese beadwork get separated from the contexts in which they were made and used. Pieces end up on the world market or in museum collections with almost no provenance. We don’t know who made them, where, when, or under what circumstances: whether for family use or for sale.

Reconstructing that provenance can be difficult indeed, the more so since few museums in China or elsewhere own examples of mainland Chinese beadwork.

Further research in museum collections might provide answers.

Photo archives, containing photos of the interiors of spacious Chinese homes in the early-to-mid 20th century might also contain clues.

All it takes is one old photo to fix this beaded valance in time and space and give us a little more context.

Til then, we can only speculate…and remember to question our assumptions.

Detail of beaded valance showing flowering vase motif flanked by four Chinese characters. The “shou” character appears above and to the right of the flowering vase. Photo: Sanders Visual Images.