Decoding an Anomalous Gujarati Chakla

(This is an updated version of a post I wrote some years back.)

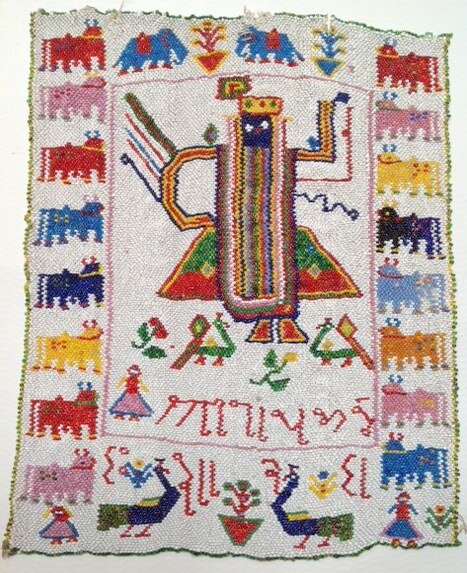

I saw a curious piece online recently. It was probably made in Gujarat State, Western India as a chakla or decorative panel to hang on the wall of a home.

But this chakla doesn’t seem typical of Gujarati beadwork, at least not the pieces I’ve seen in person or in books. I wanted to know more.

Who was the large figure in the center of the panel, looking like a woman wearing a veil - maybe a Hindu goddess or a bride?

What were the diagonal lines floating in the air near her left arm?

And the object balanced on her head, was it some kind of headdress?

Her face - why is it blue? (That should have been a giveaway but I didn’t catch on.)

The writing below the figure, what does it say? In what language? A quick Google search suggested Gujarati. But that was as far as I could get without an expert.

I pulled out my old copy of The Embroidery and Bead-Work of Kutch and Saurashtra, by J.M. Nanavati, M.P. Vora, and M.A. Dhaky (Baroda: Dept. of Archaeology, Gujarat State India, 1966). It’s the only in-depth study ever published on the beadwork of this part of the world.

Several beaded chaklas from the late 19th century are shown, all totally symmetrical in design, with a square area at the center surrounded by a border. Where there are figures of humans, animals, or deities, the figures are usually relatively small and shown in pairs or groups. The motifs are spaced at careful intervals, almost always against a white background. There are almost no inscriptions. These early chaklas embody the conventional design rules – the design code - by which Gujarati beadworkers of the era apparently operated. Most of them, at least.

But the chakla shown here seems to operate by a slightly different code, maybe because it was made in the early-to-mid 20th century. The background is still white and a border is in place. But instead of rigid symmetry and careful spacing of motifs we have a looser, more idiosyncratic, even naïve aesthetic which tolerates, maybe even cultivates disproportion and displacement.

For instance, the central figure’s feet are not quite centered under its legs; the white eyes are slightly askew; the animals in the right border are smaller than the ones in the left border; and the small female figure in the lower left corner lacks a head (or is it her torso that’s missing?).

Of course these anomalies are part of the charm. In them lie traces of the maker’s personality, aesthetic, and worldview. They tell us that this piece is authentic, the result of someone’s strongly-held feelings, not a piece mass-produced in some perfection-driven factory.

Next I checked a few more books on Indian textiles and folk art. I found nothing similar. It didn’t surprise me, because the beadwork of western India has never been adequately documented. Nor does it seem to be well valued.

It was time for a different kind of expert. So I called the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations at The University of Chicago and described my questions.

In a day or so I received an email from Mona G. Mehta, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science. She is a native speaker of Gujarati who was raised in the city of Bombay and researches the politics and society of Gujarat. She was happy to help.

Here is a brief excerpt from Ms. Mehta’s email, which I quote here with her permission.

“The central figure that you see in the bead work is not a woman but Shrinathji or a form of Lord Krishna worshipped by the Vaishnavite or Pushtimarg sect of Hinduism (started by Vallabhacharya [1479-1531] ) and is immensely popular in Gujarat. The iconography of Shrinathji is typically bedecked with lavish jewelry and fine clothing and exists in many stylized forms. The veil like thing you pointed out is actually either a garland of jewels or flowers. In the temple of Shrinathji the idol is treated as if it were a real and divine person and its clothes and ornaments are changed at particular times of the day from morning to evening….

“In fact, the particular dress of Shrinathji, with fitting pants that curl at the bottom and a long flowing tunic-like shirt, reveals the influence of the Mughal and Muslim garments Chudidaar and Kameez, versions of which are widely worn today in South Asia, particularly in north India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. This is because this sect of Shrinathji worshippers appeared around the time of the arrival of Mughal rulers in the South Asian subcontinent.

“The diagonal lines on the upper left are often flowers….or simply a piece of flowing silk. The feather on the left hand side of his crown is a peacock feather, which is the quintessential symbol of Lord Krishna.”

Ms. Mehta mentioned a Wikipedia entry that gives basic information about Shrinathji and his appearance. A Google image search produces dozens of other depictions of Shrinathji, all with the same blue or black skin that often characterizes depictions of Lord Krishna, plus links to further information.

Next, Ms. Mehta analyzed the inscription.

“As far as the inscription is concerned it is indeed in Gujarati (although it is not the most legible because the curvatures are not emphasized as they should be) and the word on top panel says ‘Shrinathji’ whereas the bottom one says ‘Sharda.’ Sharda is another name for the Hindu goddess of knowledge called ‘Saraswati.’ In this context it could also be the name of the person who made this beadwork. It is usually a woman’s name, so that is a possibility.”

Thanks to Ms. Mehta’s observations, the chakla no longer seems strange to me. But it is still an anomaly, at least by the standards of conventional Gujarati beadwork.

And it still seems unusually compelling, perhaps because it has a purpose beyond mere decoration, born, we guess, of a religious impulse: to honor and invoke a beloved deity, perhaps in hopes of receiving blessings.

We have not exhausted this piece; questions remain. I suspect we should be comparing it not to old pieces of Gujarati beadwork, but to old Gujarati embroideries and paintings that depict Shrinathji.

So the next step might be to take a look at this book: In Adoration of Krishna: Pichhwais of Shrinathji: TAPI Collection by Kalyan Krisha and Kay Talwar (Mumbai: Garden Silk Mills Ltd., 2007).

But itt’s time for me to head back to the studio and think about breaking a few rules, maybe try making a piece that transcends the decorative impulse motivating so much of my work.

Not that there is anything wrong with beauty!

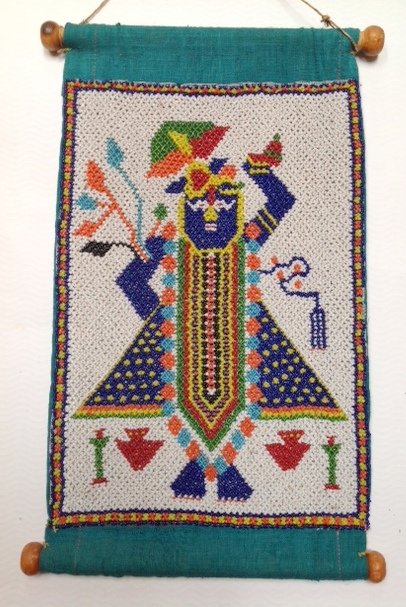

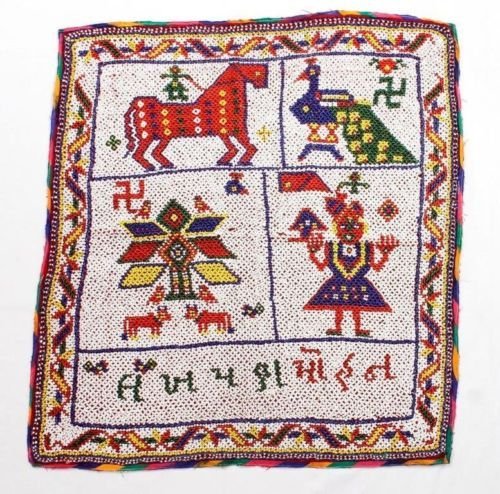

(Postscript: Recently another beaded depiction of Shrinathji appeared on the internet. It's shown below, second from right. I confess I don't find it as compelling as the one I discussed above. It's nicely done but not as inspired; it seems to follow a code. Is it a workshop piece? And another chakla with a Gujarati inscription, courtesy of the internet, shown at far right.)

(The text above is copyright Valerie Hector 2015. All rights reserved.)